|

As a result of becoming an amateur artist and being a student of the human brain, I am increasingly thinking about the potential role of visual arts in the formal education (and eventual practice) of engineers. In order to develop, share, and test my ideas, I have written and spoken about ways in which engineers, beginning as students, can benefit from studying and doing visual arts such as pencil drawing, painting (oil, acrylic, water color), and sculpture. These benefits, which I have described elsewhere1-6, include:

- Getting beyond just looking and, instead, really seeing, literally and figuratively

- Increased awareness of the capabilities of the brain’s right hemisphere

- Enhanced awareness of the role of composition in communication

Composition

Let’s consider, in some depth, the last benefit of participating in visual arts, namely knowledge and use of composition to improve communication. In the art world, composition refers to how elements or things are positioned on a painting or drawing or arranged within a sculpture. The artist, intentionally or unintentionally, uses composition to set a mood or send a message7,8,9,10. I mention unintentionally, because artists sometimes intuitively use some rules of effective composition.

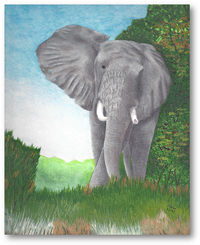

We don’t know why, but the human brain tends to respond favorably to classical composition rules traced back to at least the Rennaisance7. Consider some of these rules, using the following elephant drawing as an example.

- The rule of thirds7,8,10: Do not put the principal object in the center. The elephant is to the upper right of center.

- Gazing/walking direction7: If the principal object has a directional aspect, leave room in that direction. Ample space is provided in the front of and to the side of the elephant.

- Emphasize positive versus negative space7,10: Positive space is that occupied by the principal object and negative space is everything else. The elephant occupies a substantial portion of the drawing.

- Focal point7,8,10: Immediately bring the viewer to the principal object through the use of size, color, or other visual features. The elephant’s white tusks and large ears tend to grab the viewer’s attention.

- Odd, not even7,11: This, the last of this sampling of composition rules, recognizes that the human brain prefers an odd number of objects over an even number. Think of three pieces of cutlery, Aladdin’s three wishes, three Olympic medals, three inalienable rights, and the three colors in our flag. Given that the elephant is the only significant object, the drawing easily satisfies this odd-over-even rule. However, I submit that if we were to consider more elephants in a drawing, three or five would be preferred over two or four. (The next time you buy a flat of annuals to plant in groups around your yard, experiment with composition. Put two in one area and three in another. Which grouping do you prefer?)

So What?

If you’ve gotten this far, you may recall my claim at the beginning of this article that “engineers, beginning as students, can benefit from studying and doing visual arts,” which presumably includes composition. So, what is the benefit of understanding the art world’s composition rules? The short answer is that engineers are composers and we will be more effective if we understand and apply composing rules. We should know what kinds of arrangements are likely to be preferred by the brains of the colleagues, clients, and stakeholders we work with or serve.

Consider some examples:

- You, as city engineer, are leading the design of a new public works complex consisting of multiple buildings. Aware, that at the concept stage the configuration will need to be approved by your city council, you show an odd number of buildings or building clusters.

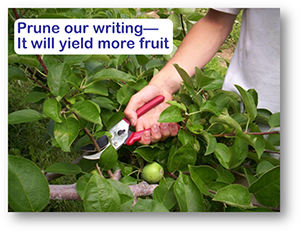

- You are leading a writing workshop for your firm and want to stress the value of carefully editing writing so as to get rid of unnecessary words. Given the importance of vision – the dominant sense – you do not use a boring text-only slide with bullets. Instead, because of your understanding of composition rules, you prepare the following strongly visual slide. It uses an off-center arm and hedge clippers, bold positive space, and a strong focal point to communicate your pruning advice.

- You are presenting, via a webinar, your recently completed draft strategic plan to your firm’s two dozen offices. After you indicate the purpose of the plan and then describe its many features, you review the key points. You summarize the essence of the entire plan with three items each described in a few words and illustrated with a meaningful and memorable image.

Notice that I used three examples. In an early draft, I had two examples but that didn’t look right.

Closure

Do you think that developing an improved sense of composition (which is one result of practicing visual arts) will enable engineers to more effectively present concepts, ideas, plans, and designs? I do. However, because my ideas are at the exploratory stage and subject to change, I would like to hear from you.

Cited Sources

1. Walesh, S. G. 2017. Introduction to Creativity and Innovation for Engineers, Chapter 7, Advanced Whole-Brain Methods, Section 7.4, Freehand Drawing, Pearson, Hoboken, NJ. (Available in North American and Global Editions.)

2. Walesh, S. G. 2017. “STEM is Good, but STEAM is Better,” Guest Viewpoint, Engineering News-Record, December 27.

3. Walesh, S. G. 2017. “Would Doing Art Make You an Even Better Engineer?” presented at the annual conference of the Indiana Society of Professional Engineers, Indianapolis, IN, June 10.

4. Walesh, S. G. 2016. “Art as Part of Science and Engineering Education?”, a webinar presented as part of Pearson’s Featured Speakers Series, Pearson Education, October 3.

5. Walesh, S. G. 2016. “Art as Part of an Engineer’s Education?”, Reunion Conference on Environmental Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, June 24.

6. Walesh, S. G. 2015. "Visual and Performing Arts and You: Never Too Late," Indiana Professional Engineer, January/February.

7. Biasotti Hooper, M. 2016. “Composition,” presented at the Venice (Florida) Art Center, January 11.

8. Krizek, D. 2012. Drawing and Sketching Secrets, Reader’s Digest Association, New York, NY.

9. Calle, P. 1974. The Pencil, North Light Books, Cincinnati, OH.

10. Hoddinott, B. 2003. Drawing for Dummies, Wiley, Hoboken, NJ.

11. Whitehouse, G. 2009. How to Make a Boring Subject Interesting, Upton and Blanding Associates, Pleasanton, CA.

Image sources: Elephant-author, pruning-BigStock

Notes:

- Want to learn more about working smarter and being more creative and innovative? Then check out my professional practice books. They are introduced here.

- Trying to resolve an issue, solve a problem, or pursue an opportunity and need help? Contact me at stu-walesh@comcast.net or 219-242-1704. I’ve “seen a thing or two” as suggested by my bio, which is available here.

Learn More About Stu Walesh | Clients Served | Testimonials & Reviews

Managing and Leading Books | Tailored Education & Training

Home | Legal Notice | Privacy Statement | Site Map

Copyright © Stuart G. Walesh Ph.D. P.E. Dist.M.ASCE

Web Site Design, Hosting & Maintenance By Catalyst Marketing / Worryfree Websites |